Written by Alice Cazzoli

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), courts in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and other courts in the Balkan region have made towards holding war criminals accountable, which is crucial for reconciliation and lasting peace. The International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP) has also played a significant role in this process.

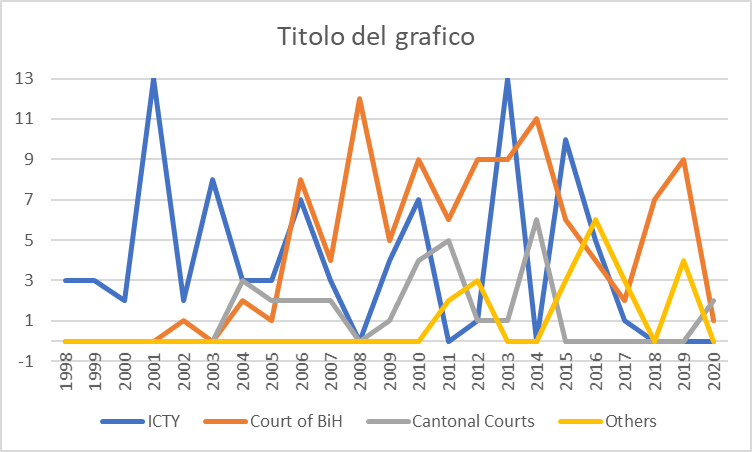

The ICTY prosecuted a total of 161 individuals who held leading military and political positions during the wars in the former Yugoslavia, with a total of 91 persons convicted, mainly for war crimes and genocide in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The majority of ICTY judgements were handed down in 2001 and 2013, and while the tribunal closed its doors in December 2017, its successor, the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Courts (IMRC), has completed or is completing the remaining cases.

Entity courts and the courts of the Brčko District Court processed war crimes in parallel with the ICTY, and with the establishment of the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the number of war crimes cases processed increased significantly. From 2005 to 2022, the Court of BiH sentenced 326 persons to a total of 3,475 years in prison.

The ICTY was established in 1993 under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations, which authorizes the Security Council to take necessary action in order to maintain or restore international peace and security (Mikyung Lee, Perl and Woehrel, 1998).

The low number of convictions during the first post-war years (1998-2000) can be attributed to the obstacles faced by the ICTY in the Bosnian context. To begin with, it was unclear if the territories of the former Yugoslavia could be considered part of the United Nations. According to some states, countries such as Serbia and Montenegro would have to apply for a new membership, while others advocated against the suspension of the FRY (Blum, 2007). In addition, there was skepticism about the establishment of the Tribunal, with some arguing that focusing predominantly on justice endangered prospects for peace (Shinoda, 2002).

Secondly, the ICTY had difficulty procuring the necessary resources and funding. Indeed, with the acceleration of workload in the Tribunal and the existence of only one permanent courtroom, it was impossible to conduct trials on schedule. Moreover, Serbia-Montenegro and the Republika Srpska were often uncooperative, which limited and hindered the timely progress of investigations (Mikyung Lee, Perl and Woehrel, 1998).

Finally, the different prosecutorial strategies used by the ICTY in some municipalities could have negatively affected the number of trials. For example, to reconstruct the chain of command in Prijedor municipality, the Tribunal put low-ranking as well as high-ranking perpetrators on trial. This contrasted with the approach taken in Srebrenica, which avoided prosecuting lower-level perpetrators (Nalepa, 2012).

Despite these initial struggles, the ICTY made considerable contributions to the development of international law and to achieving a certain degree of justice and peace in Bosnian society (Meernik, 2005).

In the beginning, the Tribunal operated according to an administerial system, whereby the trial is structured as a competition between the cases of the prosecution and the defense (Langer, 2004). However, this arrangement slowed down the processing rate, so much so, in fact, by July 1998, the Tribunal had handed down just two judgments. Because of this, the ICTY adopted a managerial system, which allowed the court to get information about the case at an early stage in the process, with the consequence of accelerating pre-trial investigations (Langer, 2004).

The ICTY was a temporary body, which was officially dissolved in December of 2017. The Dayton Agreement and the collaboration between the ICTY and Bosnian judicial institutions helped to stabilize the country (Balàzs, 2008). Initially, the BiH Constitution allotted limited powers to state institutions, giving greater autonomy to the country’s two constituent entities (Balàzs, 2008).

The early 2000s were critical for the improvement of case-management within domestic courts in BiH. The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina was established during this time with the primary goals of promoting the rule of law and establishing a Council for War Crimes, initially comprised of both domestic and international judges, to handle the rising number of cases related to accusations of war crimes (Garbett, 2010).

The criminal prosecutions that took place immediately after the conflict were widely considered unsatisfactory, with accusations of unfair trials and biased prosecutions coming from both the Republika Srpska and in the Federation of BiH. The criminal and legal processes were also complicated by the absence of a witness protection program and detention facilities (Garbett, 2010).

The Criminal Code of Bosnia and Herzegovina was passed in 2003 to address these challenges, followed by the Law on the Protection of Persons under Threat and Vulnerable Witnesses.

The international component of the War Crimes Chamber was only temporary (Garbett, 2010). As explained in the Public Information and Outreach Section of the Court of Bosnia-Herzegovina, “in the Court of BiH’s operations there were international judges working alongside the national ones, which has considerably facilitated the work on all war crimes cases, for some of the international judges had previous experience working at the ICTY” (Court of BiH, 2022).

The delegation of more cases to the Court of BiH has made it possible for a greater number of criminal prosecutions to take place (Gabrett, 2013). In fact, the BiH War Crimes Chamber has processed cases at a quicker rate than the ICTY, although these cases have notably been less complex and dealt with lower-level military hierarchy (Ivanišević, 2008).

All in all, the Court of BiH has made a sizable contribution the country’s efforts to investigate and prosecute violations of humanitarian law (Ivanišević, 2008). Through the Rule 11 bis, the cases of many lower and mid-ranking officials were handed over to the Court by the ICTY (Court of BiH, 2022), increasing the number of cases falling within its domain (Ivanišević, 2008).

This was initially challenging for the newly-established Chamber, however, international assistance on strategic prioritization of war crimes helped the Court to overcome these problems (Ivanišević, 2008). The transfer of these cases also helped give Bosnians a sense of ‘local ownership’ and greater involvement in the judicial proceedings. The Court’s local proximity was also conducive the transparency of its work, making the information from trials more accessible to local communities (Gabrett, 2010).

The collaboration between the ICTY and the Court BiH on criminal cases related to the Srebrenica genocide has had a major impact on the judicial processing of war crimes in the country. In the immediate aftermath of the war, the criteria for classifying a crime as genocide was the subject of considerable debate (Buszewski and Von Arnauld, 2013). Since the International Court of Justice formally established that the events of July 1995 in and around Srebrenica constituted genocide (The Hague Justice Portal, 2008), the process of genocide indictments and convictions has been clearer.

As a result, seven individuals were convicted of genocide by the War Crimes Chamber in 2008 for their actions in Srebrenica, followed by many more in the years to come (e.g., trial of Popovic et al. by ICTY) (The Hague Justice Portal, 2008).

For a comprehensive view of the progress that has been made concerning war crime convictions, it is important to consider the role of the International Commission of Missing Persons. Although the Commission is not part of the BiH judiciary, it has played a decisive role in holding war criminals accountable.

Nihad Brankovic, head of the Western Balkan Program at ICMP, explains that “the law on missing persons created in BiH in 2004 has been the first law of this kind in the world […] used in a country facing the issue of mass disappearance due to armed conflict” (ICMP, 2022). The law “established an institutional framework so that it prescribes and establishes the Missing Persons Institute, it strongly underlines the obligations that all state institutions, citizens and officials have to share all the information that they have on missing persons” (ICMP, 2022).

Regarding collaboration between the ICMP and ICTY towards criminal accountability, Brankovic stated that “our experts testified in some cases where we had forensics experts that were in the field for mass graves resumption and recovery of human remains for mass graves” (ICMP, 2022). The organization’s contribution consisted of “testifying in the trials about the artifacts that they found with the victims in mass graves and that were indicating that there had been a mass execution” (ICMP, 2022).

Some wonder why BiH is still dealing with war-related issues more than 27 years since the signing of the Dayton Peace Agreement. According to Brankovic, “the issue of accounting for missing persons isn’t really about resurrecting the past in my opinion and in the opinion of ICMP as an institution. It is really a part of building up the future of this or any country in this position because […] the issue of missing persons is not a resolved one but an open one” (ICMP, 2022).

The data regarding the number of criminals who were convicted by judiciary institutions in BiH show a specific pace. By analyzing the improvements of bodies such as the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina, it is possible to contextualize the above-mentioned progression. These two institutions had a troubled start due to various problems.

The ICTY encountered skepticism and some internal resistance, while the Court of BiH had to wait for a proper legal framework to be created before it was able to begin fully functioning. As a result of the many improvements in judicial practices over the years, however, the ICTY and the War Crime Chamber of the Court of BiH have made progress in convicting war criminals and set important judicial precedents. Together with the International Commission on Missing Persons, their work and commitment has had a positive impact on the peaceful reconstruction of Bosnian society.

Alice Cazzoli holds a bachelor degree in International and Diplomatic Sciences at the University of Bologna, Italy. She has worked for several years as a speaker and director for an Italian youth web radio as well as a web editor for the radio’s website. Her interests revolve around peacebuilding and the resolution of conflicts as well as human rights and migration policies. After the internship at PCRC she plans to bring on a master degree in the international relations field.