How far back can the roots of the Holocaust be traced? The events that took place from 1941 – 1945 bore a striking resemblance to atrocities carried out years before in German South West Africa. Many of the ideologies that fueled the Holocaust, as well as the means of systematic confinement and extermination of a people, began at the turn of the 20th century with the Herero and Nama. We must, thus, delve deeper into history in our effort to address consequences both costly and complex.

By Clara Ng

The 20th century saw countless milestones with regard to human advancement, including the invention of antibiotics, the automobile, rockets, and the Internet. Juxtaposed with these leaps forward, however, were the countless atrocities that would mark the 20th century as the Age of Genocide. An estimated 170 million people were “murdered by governments” between 1900 and 1999, from the Armenian genocide to the Holocaust to the genocides in ex-Yugoslavia, Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Sudan.[1]

In 1944, Polish Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin coined the term “genocide” in a book documenting the course of Nazi German rule during World War II, a word that combines the Greek word génos (“race, people”) and the Latin suffix cide (“act of killing”). Indeed, the Holocaust is perhaps the most well-known of the modern genocides and the years from 1941 to 1945 are often seen as an aberration in German history; an abrupt, unexpected lapse in its noble narrative. However, when tracing Germany’s history of colonial rule, it becomes clear that the racist ideas and rhetoric espoused during the Nazi regime were not new – they saw their inception years earlier, in German South West Africa where the near-annihilation of the Herero people from 1904 to 1906 has been recognized as the 20th century’s first genocide.

Germany’s industrialization in the 1850s was rapid. Formerly a group of agrarian, rural states, it soon boasted of railways, coal, iron, and steel. The resulting population boom led to severe poverty and urban overcrowding. As emigration increased, German national identity took a toll. This fueled an aggressive expansionism: its people needed Lebensraum, or “living space” (a notion that would later fuel the emergence of the Nazi ideology).[2] The Second Reich adopted an imperialist foreign policy, enthusiastically joining the Scramble for Africa. Beginning in 1884, Germany colonized four territories across the African continent: Togoland, the Cameroons, Tanganyika, and a coastal area in South West Africa, now known as Namibia.

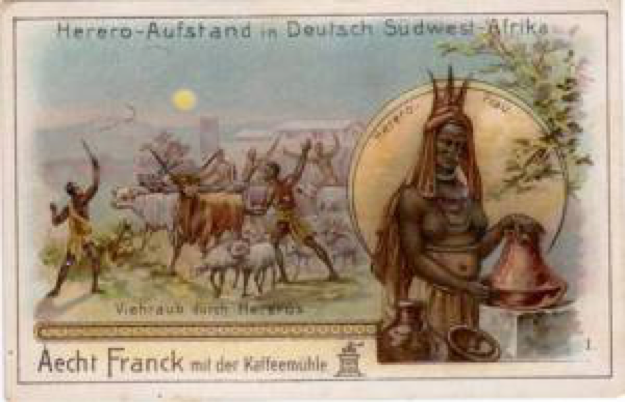

At that time, South West Africa was the only overseas German territory deemed suitable for white settlement. The German government established a protectorate over the territory, seizing control of local resources. Drawn to the lucrative diamond and copper mines, German settlers began exploiting the labor of indigenous groups: the Herero in the central-eastern region and the Nama who lived in the south.[3] There, colonial rule quickly dissolved into widespread exploitation and resource theft. Newly-settled Europeans viewed native Africans as a source of cheap labor undeserving of the same human rights as the white populations. According to the German Colonial League, for instance, the legal testimony of seven Africans was equivalent to that of one colonist.[4]

A pastoral people, the Herero saw themselves slowly stripped of their cattle and ancestral lands. By 1903, they had ceded over a quarter of their 130,000 square kilometers (50,000 square miles) of land to German colonists.[5] According to German historian Horst Drechsler, the colonists were even contemplating confining the Herero to native reserves. The situation became intolerable when construction began on the Otavi railway line that cut through the Herero heartland and paved the way for further European settlement. Their losses were augmented by rinderpest, a locust invasion, and a malaria epidemic.[6]

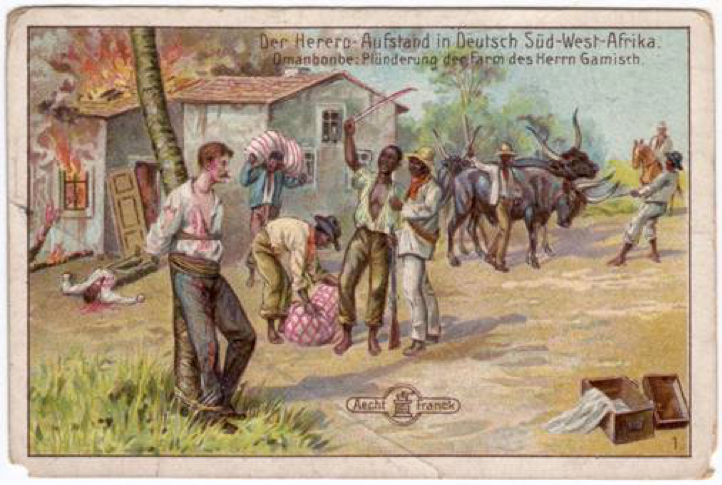

The Herero, led by chief Samuel Maharero, began to fight back against colonial expansion. In a letter to Hendrik Witbooi, the Namaqua chief, Maharero sought solidarity against the colonists, exclaiming: “Let us die fighting!”[7] Under his leadership, the tribe revolted against the Germans from 1903 to 1907, killing between 123 and 150 German landowners in a “desperate surprise attack”.[8] The Herero revolt was initially successful, but the victory was short-lived. In groups, Herero survivors retreated into the Omaheke Desert, hoping to reach the British territory of Bechuanaland where they would be granted asylum, however, most never reached their destination – they were trapped in a no-man’s land, dying by the hundreds from starvation, dehydration, and water poisoning.[9] [10] With fewer than a thousand men, Maherero eventually crossed the Kalahari into Bechuanaland, where they sought refuge with the Batswana tribe.[11] The Nama people had also joined the rebellion under the leadership of Witbooi only to suffer a similar fate.

Genocidal intent soon became apparent – it was clear that this was no longer a matter of colonial “self-defense”. Lieutenant-General Lotha Von Trotha declared the conflict a “race war”, one impossible to “conduct humanely against non-humans”. In the German media, he presented the African tribespeople as subhuman and diseased, no more than pests to be eradicated. “I think it is better that the Herero nation perish rather than infect our troops,” he wrote in late 1904. A proponent of Social Darwinism, he advocated for a radical struggle for survival of the fittest, which called for the extermination of “inferiors” in order to purify the so-called “Aryan” race.[12]

The following year, Von Trotha issued an “annihilation order” that read: Hereros are no longer German subjects. All Hereros must leave the country… or die. All Hereros found within the German borders with or without weapons, with or without animals will be killed. I will not accept a woman nor any child… There will be no male prisoners. All will be shot.[13]

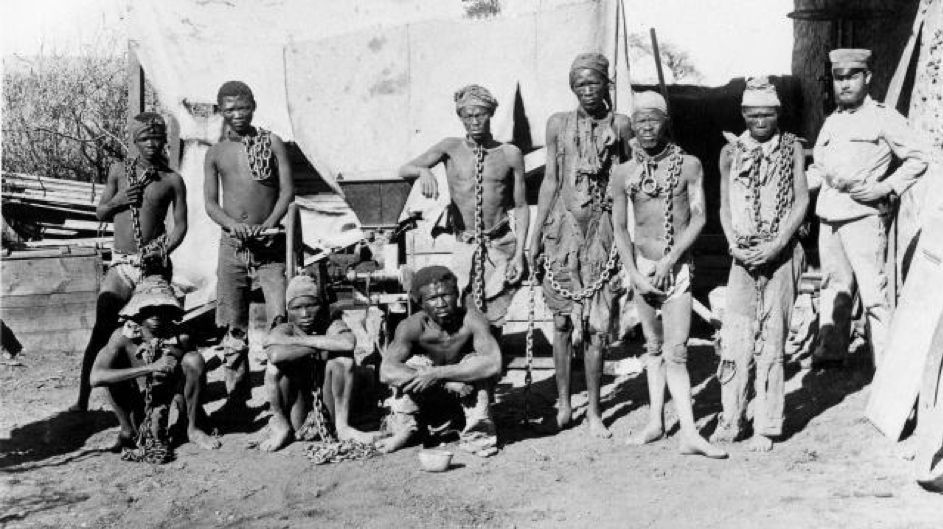

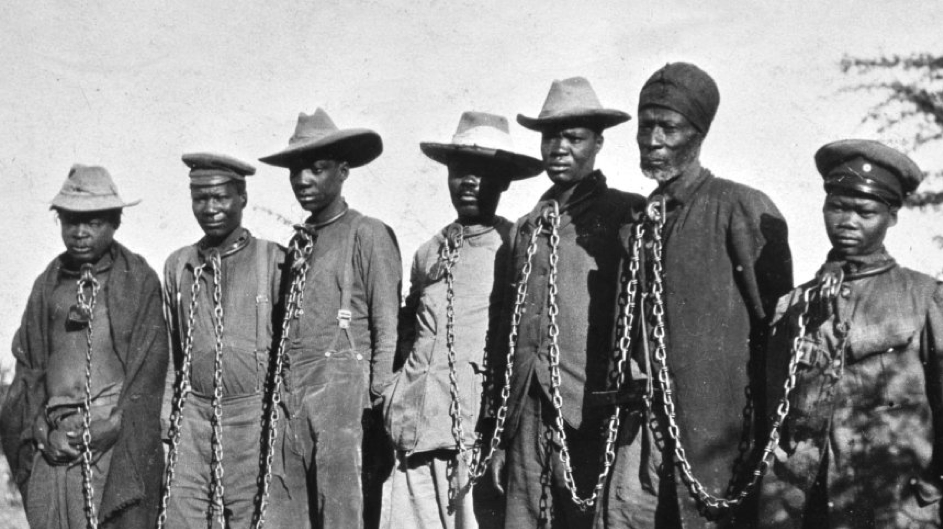

Further violence ensued, lasting for three years. By 1907, the Germans had lost several humiliating battles to the Nama, and the German public had grown tired of the conflict. Early that year, under the pressure of popular opinion, the Governor of German South West Africa, Friederich von Lindequist, declared the war officially over. By the time this order was retracted, around 65,000 Herero had perished. The remaining 15,000 survivors, mostly women and children, were interned in the official Konzentrationslage, or concentration camps, located in the present-day Namibian cities of Swakopmund, Karibib, Windhoek, Okahandja, and Lüderitz.[14] [15] Fenced in by thorn bushes and barbed wire, many Herero and Nama died from illness, abuse, and exhaustion. Later, the Third Reich would follow this model, establishing thousands of such camps where Jews and other “undesirables” were systematically killed.[16]

One of the most notorious of the Konzentrationslager was located on Shark Island in the southern harbor town of Lüderitz. The island was – and still is – barren, bound by desert and exposed to strong winds. Rations were minimal: for food, prisoners were given uncooked rice and, sometimes, the carcasses of cattle. Lung disease and dysentery were a common occurrence and often went untreated.[17] Amidst their plight, the Herero were forced into daily manual labor for private companies working on land leveling, harbor building, and railway construction projects. While at work, they were often shot at and brutally beaten with sjamboks. Death certificates were printed in bulk.[18] [19]

Few knew of the camps’ cruel conditions, but word would eventually spread. On 28 September 1905, an article appeared in the South African newspaper Cape Argus with the headline: “In German S. W. Africa: Further Startling Allegations: Horrible Cruelty.” It contained an interview where Percival Griffith, a Lüderitz transport worker, recounted what he had heard and witnessed:

The women who are captured and not executed are set to work for the military as prisoners … saw numbers of them at Angra Pequena (i.e., Lüderitz) put to the hardest work, and so starved that they were nothing but skin and bones […] They are given hardly anything to eat, and I have very often seen them pick up bits of refuse food thrown away by the transport riders. If they are caught doing so, they are sjamboked (whipped).[20]

It was clear that Shark Island was not just a labor camp – rather, it seemed functionally synonymous to an extermination camp where prisoners awaited certain death. But the horror did not stop there. Among the corpses, more than 300 skulls were collected and sent back to laboratories in Berlin for medical experimentation – most notably by Eugen Fischer, a professor of medicine and anthropology and one of the founding fathers of German (and later Nazi) eugenics.[21]

When German colonization began, the Herero numbered around 85,000 men and women. After the conflict, only about 15,000 Herero remained as forced laborers. In 1911, an official German census recorded an 80 percent reduction of the tribal population.[22] Following their defeat in World War I, Germany was stripped of its African colonies, which were then set on a path to independence.

For years, the atrocities in South West Africa were left forgotten. In mainstream discourse, the colonial victory was painted as a triumph of civilization over the racially degenerate. Military leaders were decorated and battle memoirs were published. In 1912, the Reiterdenkmal (Equestrian Monument) in Windhoek was mounted in remembrance of German achievement. There is no memorial that stands in honor of the Herero and Nama’s suffering, but mass graves still line the Swakopmund’s Swakop River and Windhoek’s railway yards.

It was in 1966 that historian Horst Drechsler first characterized the German South West African campaign as a deliberate attempt to exterminate the Herero and Nama tribes, and it wasn’t until 1985 that the United Nations’ Whitaker Report classified it as genocide. For a long time, however, Germany refused to take responsibility. Only after Namibia gained independence from South Africa in 1990 did the German government begin to acknowledge their role in the atrocities.

The violent legacy of German colonialism has been often overshadowed by the horrors of the Holocaust. While Nazi ideas and methodologies have been extensively studied, its inception in colonial South West Africa is less well-known. It was Eugen Fischer’s studies, for instance – based on his experiments on Herero and Nama prisoners – that grounded racist ideology in objective notions of science. His 1912 publication, The Bastards of Rehoboth and the Problem of Miscegenation in Man, later formed the basis of the Nuremberg Laws that legislated discrimination against Jews. “Our understanding of what Nazism was and where its underlying ideas and philosophies came from,” writes David Olusoga and Casper W. Erichsen in The Kaiser’s Holocaust: Germany’s Forgotten Genocide, “is perhaps incomplete unless we explore what happened in Africa under Kaiser Wilhelm II.”

Now it is 2018 and Namibia has been independent for 28 years. Samuel Maherero and Hendrik Witbooi are both commemorated as national heroes. Over the past century, Namibia and Germany have seen socio-political developments that shift perspectives and continue to raise new, often uncomfortable questions. Many Germans view the years from 1904 to 1907 through the historical lens of the Nazi regime, surrounded by pressures of moral redress.[23] In Namibia, it’s a different story: for many Herero, the hardships endured during colonialism sparked a century of political and economic struggle over the loss of land, resources, and cultural heritage. Their ongoing quest for reparations continues to reframe and draw international attention to this past.

Read part II of this series: “Regarding Reconciliation: The Herero’s Long Quest for Justice”

About the author: Before interning at PCRC, Clara’s undergraduate study spanned the humanities – anthropology, philosophy, psychology, and linguistics – prompting her to embark on community and education projects in South Africa, Australia, and Southeast Asia. She hopes to return for a Master’s in Comparative Literature and to help address humanitarian issues – especially those of poverty, conflict, and displacement – through journalism and research.

[1] Rummel, Rudolph J. Death by government: genocide and mass murder since 1900. Routledge, 2018.

[2] Motyl, Alexander J. “Why empires reemerge: imperial collapse and imperial revival in comparative perspective.” Comparative politics (1999): 127-145.

[3] http://jlsafaris.com/namibias-history-german-south-west-africa-herero-and-namaqua-genocide/

[4] Drechsler, Horst (1980) Let Us Die Fighting: the struggle of the Herero and Nama against German imperialism (1884–1915), Zed Press, London.

[5] Bridgman, Jon M. (1981) The Revolt of the Hereros, California University Press

[6] Drechsler, Horst (1980) Let Us Die Fighting: the struggle of the Herero and Nama against German imperialism (1884–1915), Zed Press, London

[7] Gewald, Jan-Bart, Herero Heroes: A Socio-political History of the Herero of Namibia, 1890-1923, London: James Curry Ltd (1999), ISBN 082557493, p. 156

[8] Geoff Eley and James Retallack, (2004) Wilhelminism and Its Legacies: German Modernities, Imperialism, and the Meanings of Reform, 1890–1930, p.171, Berghahn Books, NY

[9] Samuel Totten, William S. Parsons, Israel W. Charny (2004) Century of Genocide: Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts, Routledge, NY

[10] Dan Kroll (2006) Securing Our Water Supply: Protecting a Vulnerable Resource, p. 22, PennWell Corp/University of Michigan Press

[11] http://jlsafaris.com/namibias-history-german-south-west-africa-herero-and-namaqua-genocide/

[12] Haas, François. “German science and black racism—roots of the Nazi Holocaust.” The FASEB Journal 22.2 (2008): 332-337.

[13] Madley, B. (2005) From Africa to Auschwitz: How German South West Africa Incubated Ideas and Methods Adopted and Developed by the Nazis in Eastern Europe. Eur.Hist. Quart. 35, 429 – 463

[14] Gewald, J.B. (2000). “Colonization, Genocide and Resurgence: The Herero of Namibia, 1890-1933”. In Bollig, M. & Gewald, J.B. People, Cattle and Land: Transformations of a Pastoral Society in Southwestern Africa. Köln, DEU: Köppe. pp. 167, 209.

[15] Baronian, Marie-Aude; Besser, Stephan & Jansen, Yolande, eds. (2007). Diaspora and Memory: Figures of Displacement in Contemporary Literature, Arts and Politics. Thamyris, Intersecting Place, Sex and Race, Issue 13. Leiden, NDL: Brill/Rodopi. p. 33.

[16] Dedering, Tilman. “The German‐Herero war of 1904: revisionism of genocide or imaginary historiography?.” Journal of Southern African Studies 19.1 (1993): 80-88.

[17] Hull, Isabel V. (2005) Absolute Destruction: Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany, Cornell University Press, NY

[18] Jeremy Sarkin-Hughes (2008) Colonial Genocide and Reparations Claims in the 21st Century: The Socio-Legal Context of Claims under International Law by the Herero against Germany for Genocide in Namibia, 1904–1908, p. 142, Praeger Security International, Westport, Conn.

[19] Ibid

[20] Erichsen, Casper W. (2005). The angel of death has descended violently among them: Concentration camps and prisoners-of-war in Namibia, 1904–08. Leiden: University of Leiden African Studies Centre.

[21] Fetzer, Christian (1913–1914). “Rassenanatomische Untersuchungen an 17 Hottentotten Kopfen”. Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie (in German): 95–156.

[22] https://www.timesofisrael.com/groundbreaking-study-exhumes-untold-nazi-brutalization-of-womens-bodies/

[23] Melber H (2008) ‘We Never Spoke about Reparations’: German–Namibian Relations between Amnesia, Aggression and Reconciliation. In: Zimmerer J and Zeller J (eds) Genocide in German South-West Africa: The Colonial War of 1904–1908 and Its Aftermath. Monmouth: Merlin Press.