After more than a century, a minority ethnic group in Namibia insists that history be recognized: reparations are the key to restoring economic, political, and social rights. But their disorganized efforts have also curbed social reintegration and undermined tradition. The ensuing problems are multifaceted, and pose the question: what exactly is post-conflict reconciliation? Or, rather: with what, and with whom, must one reconcile?

By Clara Ng

The German colonial enterprise in South West Africa was brutal and short-lived. Twenty years after the first settlers arrived, the Herero tribe found themselves drained of resources and edged out from ancestral lands. In 1904, the Herero fought back in a series of revolts that escalated into a program of widespread ‘extermination’. In the five years that followed, they endured slavery, forced labor and repeated attempts to extinguish their culture. More than eighty percent of their tribe perished, making it the first documented genocide – and perhaps one of the most effective to date. It wasn’t until 1948, however, that the United Nations recognized genocide as a punishable crime. Now a minority ethnic group in Namibia, the Herero’s quest for reconciliation largely focuses on restorative justice and the official recognition of events.

Colonial rule in German South West Africa lasted thirty-five years. When Germany lost the First War, Namibia came under South African occupation under a League of Nations mandate. Apartheid was imposed in 1948. At that time, the Ovambo was Namibia’s largest ethnic group: comprising nearly half the population, they were represented by the Ovamboland People’s Organization, which became the South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO) in 1960. SWAPO’s frequent guerrilla attacks on the South African Defence Force won them prominence in Namibia’s liberation movement. They eventually secured independence in 1990.

Today, Namibia is one of the youngest countries in the world – a multi-party democracy with a black-majority government. The arid Namib Desert sweeps across much of the country, its vast spaces shared by a growing 2.6 million. Many are poor, and the people young – more than half of the population is not yet 25 years old. Most speak English, with minority tongues like Herero used by only 10 percent. Since independence, the economy has grown steadily through industries such as mining, tourism, and agriculture – the land abounds in metals and minerals. But despite its fertile land, prospects seem dismal for many, and even amongst the gainfully employed, alarming disparities prevail. White Namibians often earn three times as much as their black counterparts — a legacy, in large part, of the South African apartheid regime.

Material versus Symbolic Reconciliation

Sovereignty has not mended Namibia’s underlying societal and political fissures – indeed, it has opened some old wounds. Despite its solid façade, years of apartheid have written its politics along ethnic lines: the national history revolves around an Ovambo narrative, excluding Herero voices from the canon of shared nationhood.[1] Namibia’s newfound political stability has thus brought forth new priorities – such as the consolidation of national identity through a process of reconciliation. Broadly defined, reconciliation is a process through which a society moves from a divided past to a shared future. This can be done symbolically – through a collective revision of shared histories – or materially, through legal compensation paid by parties responsible. Such acts of reconciliation indicate a collective commitment to justice, human dignity and the restoration of trust.[2]

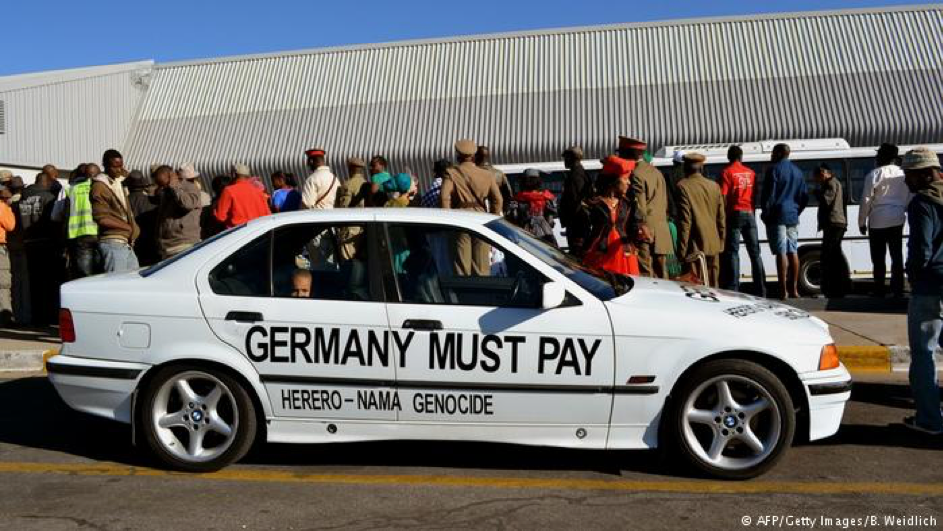

The Herero’s path to reconciliation has proved difficult. To start, their very history – and the suffering they endured at colonial hands – is often sidelined in officially-sanctioned narratives of the past. This is not surprising: since independence, SWAPO has relied heavily on German development aid. Thus, for the economically-marginalized Herero community, transitional justice entails some measure of legal compensation – specifically, from the German government and corporations involved in the colonial enterprise. Amongst a litany of legal concerns, land restitution remains one of the most salient: historical claims are often ignored, and SWAPO-supporting Ovambo candidates are given resettlement priority. As a result, many privately owned commercial farms still remain in the possession of German-speaking farmers – a substantial barrier to the socio-economic advancement of minority groups. Dispossessed and resentful, some resort to violent land grabs of white-owned farmland, fueling already-prevalent tensions.

While some of their efforts have misfired, the Herero’s quest for symbolic reconciliation has seen some success. One facet of identity is often expressed through one’s fashion choices – this is no different for the Herero community, who seek to reclaim a contentious history. On special occasions, Herero women don flamboyant Victorian gowns popular in the late nineteenth century, while the men wear suits or cavalry uniforms. These costumes – often hand-sewn in a patchwork of pattern and color – have become a powerful symbol of ethnic pride. As a gesture of historical defiance, the Herero borrow European custom in order to subvert a colonial legacy. In their quest for symbolic reconciliation, fashion proves a formidable tool.

Through such symbolic resistance, the Herero welcome the possibility of a subversive post-colonial narrative. Formal acknowledgment – an act of restorative justice that can shift a problematic historical dynamic – can also help shape a new narrative. In 2001, the Herero People’s Reparation Corporation sued the German government for their deliberate, large-scale damage to the Herero community – a burden now borne by their descendants. The case was eventually dismissed, but, in 2004, the German Minister for Economic Cooperation attended the centenary of the first Herero uprising. In a gesture of remorse, she apologized for what she acknowledged was, indeed, ‘genocide’. Another act worth noting was a 2011 visit to Berlin by tribal leaders to collect the skulls of 20 Herero people who had died under colonial rule. These events briefly spotlighted the Herero community’s concerns in the international media, as well as their demand that history be recognized.

The Herero have taken big steps toward symbolic reconciliation – on a diplomatic, as well as a historical, level. But to the dismay of local reparations activists, their promise of material redress has not been fulfilled. Germany’s apology did not prompt a direct policy change towards issues of compensation. Neither did it channel local support into the Herero cause – the government would not jeopardize a vital source of development aid (totaling about 500 million Euros since independence). Indeed, Namibia holds one of the world’s largest wealth divides – it is not small communities who benefit from international funds, but SWAPO strongholds clustered in the north. More than a century after the conflict, it seems that the problem of reparations looms large.

Some fear a domino effect – a successful reparations case could provoke a slew of similar claims. While Germany can afford such a burden, the same costs for other European governments would be quite serious: “The leaders in Paris, Lisbon, London, The Hague, and Brussels would not be amused,” notes Henning Melber, a German-Namibian political activist. Even so, loopholes can be found – such as admitting guilt while minimizing costs by limiting compensation to a select few. In 2013, for instance, the United Kingdom agreed to compensate Kenyans who had been tortured by British colonial forces during the Mau Mau rebellion in the 1950s. Not long after, The Netherlands paid reparations to the families whose fathers died in 1947 during colonial rule.

Symbols of Unity and Division

It is not surprising, then, that disorganized attempts at reconciliation continue to undermine traditional symbols of unity. On Okahandja Red Flag Day, held in August, the Herero people gather to commemorate their chieftains who died under German rule. The three-day ceremony – involving a procession to numerous graves, followed by a church service – affirms Herero memory in the face of a turbulent past. Recently, however, Red Flag Day has been repeatedly disrupted: in 2012, the annual event was postponed for the first time in 89 years. Clashes arose from the Herero’s increasingly vocal claims to compensation and the tensions that had been building amongst the different factions. Once a symbol of solidarity, collective remembrance, and communal strength, Red Flag Day now threatens to spark division and dissent.

But historical trauma is not just a psychological phenomenon – it leaves behind tangible scars in our physical realm. Swakopmund is the center of Namibia’s German-speaking minority – a tourist hub famous for its scenic coast and colonial architecture. Its history is lesser known: it was in Swakopmund that so many were worked to death in one of the four colonial concentration camps. In the gardens of its State House, a German marine clutches a rifle and stands guard over a dying comrade – this is the Marine Denkmal (or Marine Monument), which commemorates the German efforts against the 1904 uprisings. Having stood in its place for 107 years, it is now smeared with red paint, a gesture of protest by the recently-formed Back to Germany Activist Movement. Representing the local Ovaherero, Damara, and Nama-speaking resident communities, the organization approached the International Criminal Court (ICC) in 2016 to lobby for its removal.

Leading the lobby group is Laidlaw Peringanda, a human rights activist with Herero roots. In an interview with a journalist, he made a striking comparison to the 1965 event that collapsed an entrenched East-West divide. “Where is the Berlin Wall?” Peringanda demanded. “It is gone because it represented the ugly and brutal past of Germany. We should also be allowed to remove whatever reminds us of the painful past of colonial conquest and genocide. There is no place for [the monument] in Namibia… as long as it still stands Namibians will never get the true feeling of independence.” Indeed, landscape is intimately tied to identity – erasing selective markers of a victor’s history is one of the ways that the Herero are reclaiming their own. But it is also these visible markers that yield much of Namibia’s tourist revenue. A sad irony, perhaps, that for all Namibia’s economic success, it is this grim past that frames its growth.

Examining the Broader Implications of Justice and Reconciliation Processes

Perhaps the problem is the ease with which we forget, fail to see, or neglect to examine: genocide does not end with extermination but with the need to address denial. Recently, Usutuaije Maamberuam, President of the South West Africa National Union, made a plea that the Independence Museum, located on the grounds of the former Orumbo rua Katjombondi concentration camp, be renamed the Genocide Remembrance Center. In a moving speech, he stressed the need for collective remembrance. “[Denial] is the most diplomatic stage of genocide,” he said. “It is the calmest, it is the most academic, it is the most imaginative and the most eloquent and yet in the same breath it is by far the deadliest.”[3] Decades later, many post-conflict societies are still grappling with this last stage, and, for Namibia, a young population, long history of violence, and lack of transitional justice mechanisms have proven obstacles to successful reconciliation.

In Namibia, law has not fully made peace with history – thus far, the ineffectual pursuit of justice through litigation testifies to the complexity of the process and ambiguity of the concept itself. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, it is institutional reform, or the lack thereof, that threatens post-conflict state-building. Progress is obstructed by rigid territorial and political divides – a legacy of Dayton – as well as disputes concerning internal state construction.[4] The lack of common narrative entrenches ethnic divides along the lines of contested recent history. The last two decades prompt the question as to whether the political, legal, and institutional lines drawn in Bosnia can endure in a sustainable quest for peace.

In the pursuit of transitional justice, legislation is often the mechanism for resolving historical injustices, but legal remedies often rely on the politicization of memory.[5] Law can easily write and rewrite history – at the high cost of silencing dissent, obscuring other voices, and administering a notion of fairness that may not hold for all. The neat binaries required by the courtroom — right versus wrong, truth versus lie, victim versus perpetrator — may diminish the complexities, ambiguities, and complicities found in the archives of oral and written memories.

Reconciliation involves rethinking old emotions and attitudes, rebuilding relationships, and confidence in a shared future. While a useful conceptual framework, theory, and practice are so often misaligned. Maybe the very notion of reconciliation warrants closer scrutiny: its implementation is often transient, superficial, and short-sighted. It may be appropriated as an ideological tool rather than an institutional process. It may even reflect and reinforce existing structural divisions.[6]

Perhaps this definition of reconciliation would prove more useful: a transformative fiction that confers a moral unity upon the related events.[7] Reconciliation is not an empirically-defined, quantifiable end-state but a vague and elusive process – its success calls for a deeper understanding of the complex relationships between truth, justice, healing, and peace.

Read part I of this series – “The 20th Century’s First Genocide: Not the Holocaust, but the Herero“

About the author: Before interning at PCRC, Clara’s undergraduate study spanned the humanities – anthropology, philosophy, psychology, and linguistics – prompting her to embark on community and education projects in South Africa, Australia, and Southeast Asia. She hopes to return for a Master’s in Comparative Literature and to help address humanitarian issues – especially those of poverty, conflict, and displacement – through journalism and research.

[1] Hamrick, Ellie, and Haley Duschinski. “Enduring injustice: Memory politics and Namibia’s genocide reparations movement.” Memory Studies (2013): 1750698017693668.

[2] Nadler, Arie, and Tamar Saguy. “Reconciliation between nations: Overcoming emotional deterrents to ending conflicts between groups.” The psychology of diplomacy (2004): 29-46.

[3] Hamrick, Ellie, and Haley Duschinski. “Enduring injustice: Memory politics and Namibia’s genocide reparations movement.” Memory Studies (2013): 1750698017693668.

[4] Cox, Marcus. “State building and post-conflict reconstruction: lessons from Bosnia.” Geneva: Centre for Applied Studies in International Negotiations (2001).

[5] Bargueño, David. “Cash for Genocide? The Politics of Memory in the Herero Case for Reparations.” Holocaust and Genocide Studies 26.3 (2012): 394-424.

[6] Little, Adrian. “Disjunctured narratives: rethinking reconciliation and conflict transformation.” International Political Science Review 33.1 (2012): 82-98.

[7] Moon, Claire. “Narrating political reconciliation: Truth and reconciliation in South Africa.” Social & Legal Studies 15.2 (2006): 257-275.